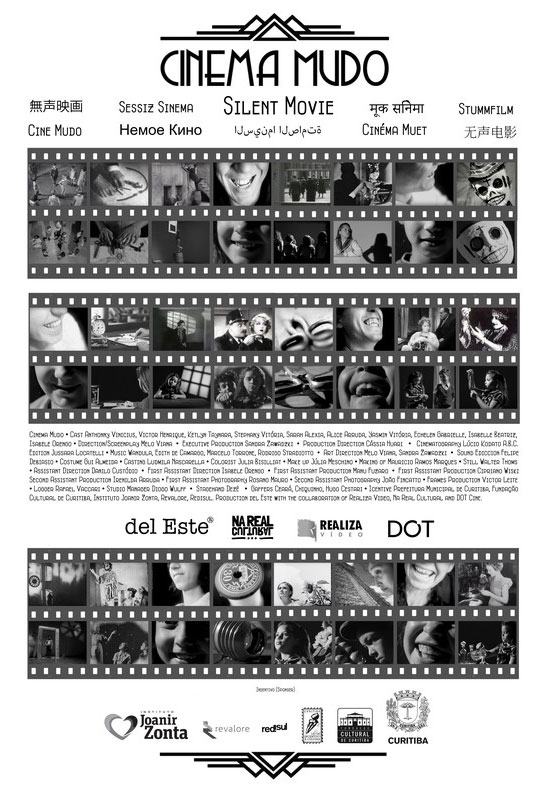

Silent Movie

Silent Movie

Genres: Drama

Runtime: 15 minutes

Watch Trailer

The “Cinema Mudo” project is the realization of a short film and at the same time helping and integrating residents of a community living in a high-risk area. All children (actors and actresses) who work in the movie are residents in the community Vila Torres, an at-risk area in Curitiba. They were chosen after a theater classes for children held in that community as part as the film project.

Most of the residents of this community live from the collection and recycling of garbage in the city of Curitiba.

The story shows three children (two boys and a girl), in the mid-thirties, setting up a movie frame projection room. They build a projector with an empty shoe box with two holes with the size of a film frame. Inside the box they put a burnt-out bulb without its filament and filled with water. This bulb is used as a lens. Children had to wait until the bulb burned out. Those electrical bulbs were rare in those days.

Children visit the city’s cinema, dig through the trash in the screening room and collect pieces of film for their projections. When the children are going to do the test with the projector, the girl, in charge of filling the bulb with water, let it fall and the bulb breaks. The boys are not happy. After dreams and expectancies, the girl gets another bulb and the projector is ready.

On the day of the presentation they invite friends to watch the projection. The sun does not appear and the children are distressed. But, at last, the sun and the light appear and the projection is made.

In a dark room a ray of light passes between two tiles. With a piece of mirror one of the children reflects the sunlight through one of the holes in the shoe box. The sunshine passes through the frame, passes through the lamp with water and projects the image on the wall.

The short film proposes, as a background, to expose the history of cinema from the transition between silent and spoken cinema. This exhibition is made through the frames with references to the most representative films of the transition, covering the specific period between 1930 and 1934.

The photography of the film is based on films from this period directed by filmmakers such as Humberto Mauro, Charles Chaplin, Ardeshir Irani, Mário Peixoto, Carl Theodor Dreyer, Yasujiro Ozu, Josef von Sternberg, Luiz Buñuel, Kenji Mizoguchi, Jean Vigo, Cecil B. DeMille, Mark Fric, Carl Lamac Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, Zhang Shichuan, Yakov Protazanov, Victor Sjöstrom, René Clair, W. S. Van Dyke, Leitão de Barros, René Clair, Aleksandr Dovzhenko, Sergei Eisenstein, Orestes Laskos, Alessandro Blasetti, Manuel de Oliveira, Jean Renoir and Fritz Lang.

It is known that with the advent of sound in cinema, which occurred in the years 1926/1927, some directors resisted the new technology. City Lights, by Charles Chaplin, performed in 1931, four years after The Jazz Singer, was still mute. The Vampire, by C. Th. Dreyer, performed in 1932, followed Chaplin’s resistance. Yasujiro Ozu made his first spoken film only in 1936. His compatriot Mizoguchi had already experienced sound in his first film “Fujiwara Yoshie no Furusato”, in 1930.

In L’Atalante, 1934, Jean Vigo, despite being his 3rd. sound film, preserves the structure of a silent movie. The character Jean after losing his beloved Juliette, remains 23 minutes without speaking in the film. The sequence is a “silent film” within the “spoken film”.

Cecil B. DeMille, one of the founders of Paramount Pictures Corporation and, therefore, having the technology available, appropriates the sound only in Madame Satam, from 1932. Sjöstrom only debuted his first spoken film in 1930, A Lady to Love. When he returned to Sweden in 1937, he still made two silent movies.

In Ganga Bruta, from 1933, Humberto Mauro used some dialogues, but the film is essentially silent. In Limite, 1931, Mário Peixoto, in addition to making a silent film, uses only a small dialogue with signs, making the film absolutely silent. That same year Ardeshir Irani directed India’s first spoken (and sung) film, Alam ara. Still in 1931, Leitão de Barros made his first spoken film in Portugal, with a screenplay by René Clair: A Severa.

That year, in Russia, Dovzhenko performed Terra, still silent. The father of Russian cinema Yakov Protazanov had made his first sound film a year earlier, The Miracle of Saint George. The Vasilyev brothers started their careers in 1930 with a silent film Spyashchaya Krasavitsa. In 1932 they made Lichnoe Delo, a mixture of silent and sound cinema. Only in 1934 did they make a truly talked-about film, Chapaev. In that year Manuel de Oliveira made his first cinematographic work, the short documentary (silent) Douro, Faina Fluvial. Sergei Eisenstein had already experienced sound in cinema, but when he made ¡Qué viva México!, in 1932, he preferred, however, to make it silent. Vsovolod Pudovkin’s transition film was The Defector in 1933. A year earlier, the wizard of silent film editing Kulechov started his sound films with “The Horizon”.

Mark Fric directed with Carl Lamac in 1931, in Czechoslovakia, “On a Jeho Sestra”, the 1st. spoken film of the directors. Josef von Sternberg made in 1929 Thunderbolt, a film with a double version: one spoken and the other silent. In 1930 he made Blue Angel, this one appropriating the sound fully.

Fritz Lang and Jean Renoir made their first films spoken in 1931 “M” and “La Chienne”, respectively, incorporating sound as a cinematographic language. The same had already done Hitchcock with Blackmail, 1929, his first spoken film. But, Hitchcock, that same year, still made the silent film The Manxman.

Of the 55 films directed by the Greek Orestes Laskos, two were made in the 1930s, both silent. The first was Dafnis and Cloé in 1930. In Italy, Alessandro Blasetti and Mario Camerini began their cinematographic careers with a silent film from 1929. In 1930 Blasetti directed Nerone, the first spoken. The first spoken film in Mexico was “Más Fuerte que el Deber”, directed by Alexandro J. Sevellia, in 1931. The Italian-Argentine Mario Parpagnoli, who directed 30 films, made his last, still silent, in 1930, the musical drama “Adiós Argentina”.

In 1930, Zhang Shi Chan made China’s first spoken film: Sing-song Red peony. In that year Boreslaw Newloyn made his only film and the first spoken film in Poland: The Moral of Mrs. Dulska. In the same year, in Denmark, George Schneevoigt performed Eskimo, already spoken.

Many directors have not adapted to the advent of sound, some have ended their careers. Others incorporated sound into their films as part of their cinematic language. After all, as Béla Balázs said, cinema is the only art in which silence is possible.

In addition to direct references to these directors, there are many references to Russian director Andrei Tarkovski. These are, sometimes in the image, sometimes in the audio. The sound of the printing press is mixed with the sound of the train from the movie Stalker. The framing of the girl at the desk with a clock (replaced by an hourglass) in front of her is a reference to Sacha in The Steamroller and the Violin. In turn Tarkovski made reference to Yasujirô Ozu in Passing Fancy. The sound of the rain on the apples is the sound of Stalker, when the three characters talk while sitting on the water in the Zone.The rain on the apples is a reference to Ivan’s Childhood, which, in turn, refers to Earth by Dovzhenko.

The street sounds in the Cinema’s door scene were used sounds from the 1930s from Nanking (China) Brussels, Naples, Damascus and London.

Credits

Director/Writer – Melo Viana

Producer – Sandra Zawadzki

Key Cast

Anthonny Vinicius

Victor Henrique

Ketlyn Taynara

Stephany Vitória

Sarah Alexia

Alice Arruda

Yasmin Vitória

Echelen Gabrielle

Isabelle Beatriz